For the past two years, Colombia has topped the global ranking of countries with the most land and environmental defenders murdered, a ranking conducted by Global Witness. Last year, 79 people who dedicated their lives to these causes were reported killed; Brazil and Honduras followed with 25 and 18 victims, respectively. In 2022, Colombia also had the highest number: 60 Colombian defenders were killed.

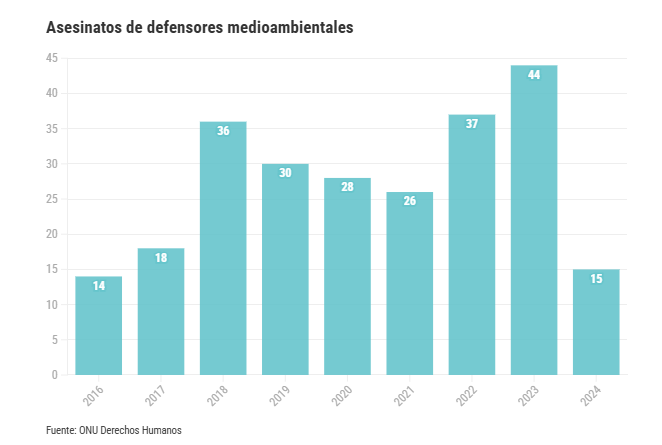

This level of violence against those protecting nature is not incidental. Between January 2016 and September 2024, UN Human Rights verified the killing of 248 environmental defenders.

"89 percent of the documented homicides were of Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and peasant defenders, showing the disproportionate impact of violence on communities that inhabit the most biodiverse territories and defend nature, natural resources, their lands, territories, ways of life, and culture. Among these cases, 139 were Indigenous people, 18 were Afro-descendants, and 64 were peasants," states the most recent report from this UN agency.

The UN agency reports that these murders have been increasing since 2016 and have concentrated in the departments of Cauca with 76 cases (31 percent of homicides), Chocó with 23 (nine percent), Nariño with 21 (eight percent), Valle del Cauca with 18 (seven percent), Antioquia with 15 (six percent), and Norte de Santander with 8 cases (three percent).

These deaths usually occur in hostile environments, not only due to the dynamics of armed conflict in different regions of the country and state neglect but also due to the stigmatization faced by those who defend natural resources.

Regarding the accusations, UN Human Rights makes a clear call: "That national, departmental, and municipal authorities refrain from stigmatizing and combat stigmatization through informational and recognition campaigns against defenders of the environment."

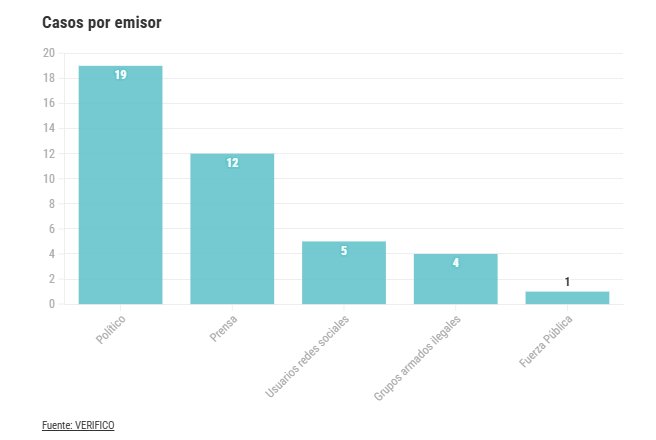

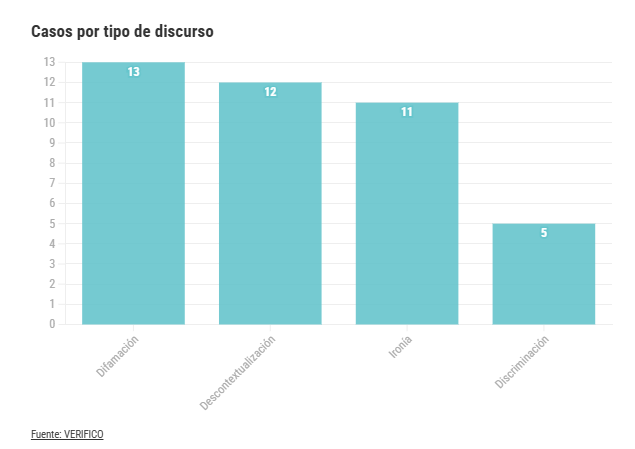

Since June 2023, this portal has fact-checked misinformation and stigmatization against human rights defenders, analyzing 70 statements and insinuations made by sectors with influence on public opinion. Of these, 41 are related to sectors dedicated to defending the environment and the territories of ethnic communities.

Most, 30, are against Indigenous communities, who have been accused by politicians, journalists, media outlets, and illegal armed groups of hoarding land, being unproductive, violent, and part of the armed conflict.

We are also analyzing a case of stigmatization against Afro-descendant communities who mobilized to demand proper implementation of Law 70, which defines the formation of community councils where they live.

Three cases involving officials from the current national government have been verified. All are related to the actions of the “Save Gorgona” Committee, which opposes the construction of a military base on the island of Cauca due to potential ecosystem damage and advocates for respect for the right to prior consultation for Black communities, whose members were accused of being tied to drug trafficking. These insinuations were made by the President of the Republic, Gustavo Petro; the Director of the Department of Social Prosperity, Gustavo Bolívar; and the former President of Congress and current ambassador in London, Roy Barreras.

Opposing large-scale legal mining is also a cause for stigmatization. In the Nordeste and Suroeste regions of Antioquia, VERIFICO found four cases of harassment via social networks.

Two more cases of stigmatization and misinformation are related to a protest at the headquarters of the oil company Emerald Energy in Los Pozos, San Vicente del Caguán, which escalated and ended with the death of a protester and a member of the Police Mobile Anti-Riot Squad. This was labeled a guerrilla takeover and kidnapping by Senator María Fernanda Cabal and former Minister Juan Camilo Restrepo, respectively.

There are also threats and stigmatization from illegal armed groups against organizations dedicated to environmental defense. One was made by a paramilitary-origin group and the other by a FARC dissidence.

The 41 cases fact-checked demonstrate that those who defend nature are stigmatized by sectors with different ideologies and political affiliations.

Stigmatization and its effects

Environmental defenders unanimously respond that the main reason they are stigmatized is because they are seen as supposed opponents of development.

"Unfortunately, in Colombia, defending nature generates risks. We have been labeled as obstacles to development and progress because we report and monitor companies that extract oil and gas in the territory," says Óscar Sampayo from the Yariguíes Regional Corporation, which advocates in the Magdalena Medio region.

Ethnic peoples are also targeted for demanding respect for prior consultation and blocking industrial projects in their collective territories. Richard Moreno, coordinator of the Afro-Colombian National Peace Council, notes other narratives accusing them of hindering progress in rural areas: being opponents of wealth, lazy, and conservationists while facing hunger.

However, for this human rights defender, who also leads the Chocó Interethnic Solidarity Forum, these accusations stem from ignorance of a life view that departs from an extractive, accumulative, and disrespectful model toward territories.

"What kind of wealth are we talking about? The kind that accumulates in the hands of a few and impoverishes many? No, that's not the one we want," Moreno says. As for accusations that ethnic communities are lazy and overly conservative, he responds, "It’s one thing to respect the territory and seek rational, responsible use of natural resources, and another to exploit it irrationally as others want to."

These perspectives are shared by Aída Quilcué, an Indigenous leader from Cauca who has been a senator for two years. "We consider nature a living being, which we must protect. That does not mean that Indigenous people have not contributed to the country. On the contrary, thanks to Indigenous people, we have the biodiversity we have today."

Andrés Pachón, a spokesperson for the “Save Gorgona” Committee, has frequently been questioned by the current national government for opposing the expansion of military facilities on the Pacific island, stating that when environmental defenders aren’t accused of opposing development, they’re accused of alleged ties to illegal armed groups.

"The most common messages are that we are being used or are tools of different groups. So, we are often told that we represent the interests of drug trafficking because we oppose a Coast Guard base in a National Park and one of the most biodiverse places in the world," he notes.

These messages not only encourage violence against those defending the rights of marginalized communities and territories but also cause delegitimization and friction within the social processes they lead.

Astrid Torres, coordinator of the Somos Defensores Program, an organization that has monitored all types of aggression against social leaders for 25 years, warns that labeling environmental defenders as opponents of development or representatives of illegal interests is serious because it affects their representation in territories.

"When a leader, an organization, or a social process is told, 'You are against development!' in highly vulnerable areas, it generates strong conflicts because communities may perceive it as hindering jobs, roads, school supplies, and all the benefits that corporate social responsibility offers," Torres explains.

These accusations also create external or direct harm to human rights defenders. "Stigmatization generates intimidation against the person and their family. It comes from defamation, slander, and libel, often accompanied by fake stories and profiles on social media, aimed at destroying and undermining the credibility of environmental human rights defenders," says Sampayo, who had to leave Magdalena Medio in 2021 due to threats he received from stigmatization for reporting river pollution.

Finally, stigmatization has also reached judicial levels, as some activists have faced lawsuits for protesting against large projects.

Farmers sued by AngloGold Ashanti

For 14 years, farmers and environmental leaders in Jericó, southwest Antioquia, have defended the territory against South African mining company AngloGold Ashanti, which seeks to turn this coffee and agricultural area into a mining district. The project, named Quebradona by the company, aims to extract copper and other minerals.

However, the Southwest is not a mining region; rather, it supplies food to much of the department, boasts ecological diversity, and has abundant water sources. In 2010, when AngloGold arrived in Jericó, farmers from the La Soledad area noticed a decrease in water flow due to the company’s soil drilling for exploration.

Fernando Jaramillo, coordinator of the Jericó Environmental Committee, says this triggered the community’s organization, and they have since prevented mining from establishing in any of the five identified sites with copper deposits in the municipality.

The company, Jaramillo notes, has only managed to create an extensive advertising and propaganda campaign that has weakened local resistance. "For several municipal administrations now, there hasn’t been a single social, cultural, or sporting event not sponsored by the mining company, and, logically, all these activities carry a very strong promotional component that attacks territorial defense and some individuals," he says.

The social media propaganda has led to stigmatization against farmers, students, activists, social communicators, artists, religious figures, and all those opposed to the mining project. Jaramillo says many of these messages come from people in Jericó who are “highly committed to the mining company because they receive some benefit. There is also a number of bots on social media accusing us of being linked to armed groups like the ELN."

Another attack from AngloGold against environmental leaders and farmers in Jericó includes lawsuits for two specific incidents in which the company was removed from the territory. The first was in November 2022 when mining company workers arrived at a coffee property in the Vallecitos area to prepare the installation of a mining drill platform. “A protest began, and from that moment, 45 people, including minors and the elderly, were sued,” Jaramillo recounts.

The second complaint was filed in December 2023 when AngloGold brought machinery into the La Soledad district and set up a mining platform. Farmers and land defenders entered the property and dismantled it. At that time, 61 farmers were accused.

After several public hearings that were suspended and postponed, the defense of the affected parties requested the annulment of these complaints. On September 19, 2024, during the latest hearing, the Police Inspector denied the request and rescheduled the trial for November 25.

This situation has caused tension among the more than 80 accused farmers and their families. However, the commitment to defend their land has grown, and more social sectors join the struggle each day. Jaramillo says that over the past 14 years, they have managed to ensure that community responses remain peaceful. “We have not created confrontations, nor have we become extreme. On the contrary, we have tried to be respectful and clear with arguments as to why we defend water and land.”

The farmers of Jericó and the other 23 municipalities in the southwest are hopeful that this government will support the idea of turning the region into an agroecological district and designating it as a protected area for food production or that they will be covered by Decree 004 of 2024 from the Ministry of Environment, which would declare temporary natural reserve areas in various parts of Colombia as part of environmental and mining regulations.

These temporary areas, according to Jaramillo, would be a major step forward and provide relief for five or ten years, allowing them to continue organizing in defense of their land without any threats. “The goal of this decree is to create a space for scientific and technical studies that demonstrate, in compliance with a State Council ruling, which areas are suitable for mining and which should be protected due to their wealth of natural resources.”

If you know of any case of misinformation and stigmatization against human rights defenders, please send it to contacto@verdadabierta.com to be analyzed by the VERIFICO team and included in their database.