Originally published by Alma Preta Jornalismo here.

Disinformation is a silent threat to public health, especially for the black population in Brazil. In a country where racial and social inequalities still dictate who has access to information and quality services, the spread of fake news about vaccination deepens an already alarming problem: low vaccination coverage. To give you an idea, around 23% of parents in the country did not vaccinate their children even when they went to the clinic, a rate of 17% among white people and over 29% among black people.

For black and poor communities, historically marginalized, the impact is even more devastating, putting lives at risk and perpetuating a cycle of exclusion that dates back to the slavery period.

The data comes from a study conducted by the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) and the Faculty of Medical Sciences of Santa Casa de São Paulo, published in August 2024 in the Epidemiology and Health Services Journal and released by Agência Bori. The research also shows that black mothers face almost twice as many difficulties in vaccinating their children compared to white mothers.

The study highlights racial inequalities in childhood vaccination, especially during critical developmental periods, such as at 5, 12 and 24 months of age. At these times, essential vaccines are administered, including the MMR vaccine (which protects against measles, rubella and mumps), hepatitis A and rotavirus.

The main challenges identified include the shortage of vaccines, the closure of immunization rooms and the lack of health professionals. In addition, 7% of guardians reported difficulties in taking their children to vaccination centers, whether due to lack of time, transportation problems or other obstacles. These challenges disproportionately impacted the black population, which faced 75% greater barriers compared to the white population.

Another relevant fact shows that almost half of the children were late in receiving at least one vaccine by the age of five months, a rate that rises to 61% by the time they reach one year of age. The survey also indicates that this situation is more frequent among children of black and brown mothers, reinforcing the disparities in access to immunization.

Disinformation, a practice characterized as the intentional dissemination of false or decontextualized information, with the aim of causing harm or benefiting someone, harms the vaccination process throughout society, but its impacts are even more severe in black and peripheral communities.

In Brazil, the last country to abolish slavery, the legacy of inequality in access to health makes immunization a particular challenge, intensified by the scarcity of reliable information and the spread of misleading narratives about the efficacy and safety of vaccines.

The publication “The return of disinformation about vaccines”, from February 26 to March 21, 2023, by the Laboratory of Internet and Social Network Studies (NetLab) of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), helps to clarify who finances and wants to take advantage of the dissemination of misleading discourse on the subject.

Among the most prevalent disinformation narratives, according to the study, the claims about the side effects of vaccination and the promotion of natural immunity as an alternative stood out. There are also signs of a possible connection between content from extremist groups, which combine scientific denial with the spread of conspiracy theories.

The study indicates that, as the country moves into a new phase in the fight against Covid-19, it also faces a renewed wave of misinformation. One example cited in the publication is the National Vaccination Movement, which began on March 27, with President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) receiving the bivalent dose against Covid-19.

The event, which was widely publicized, provoked several reactions on social media and triggered a rapid spread of misinformation on several platforms. This content revived old anti-vaccine narratives, intensified especially in response to the new phase of immunization.

During the period analyzed, platforms such as WhatsApp, Telegram and websites specialized in misinformation stood out for perpetuating a constant debate, amplifying the spread of misleading messages.

Regarding portals, the study states that the Dunapress website gained prominence for publishing false information, suggesting a possible international articulation in the dissemination of misinformation. One of its publications claimed, without scientific basis, that mRNA vaccines could cause “brain and heart damage”.

However, the World Health Organization (WHO) denies the information and confirms that there is no evidence to support this claim. According to the study, the same material, including the same image, was reproduced by far-right portals, such as the American The Epoch Times and the Swiss Uncut-News, contributing to the spread of misinformation.

According to the analysis of the survey, shortly after the federal government's campaign, 6.7 thousand messages were identified on WhatsApp that denied the effectiveness of the vaccines, based on false international studies that claim, without foundation, that vaccines cause heart attacks and infant mortality.

One example of this are WhatsApp groups that disseminated messages without scientific basis, associating Covid-19 vaccines with the deaths of children and artists, such as Brazilian musician Bebeto Castilho and South African rapper Costa Titch, both victims of sudden illness. However, according to the document, there is no evidence linking these deaths to vaccination. Even so, conspiracy theories continue to spread on social media, fueling misinformation.

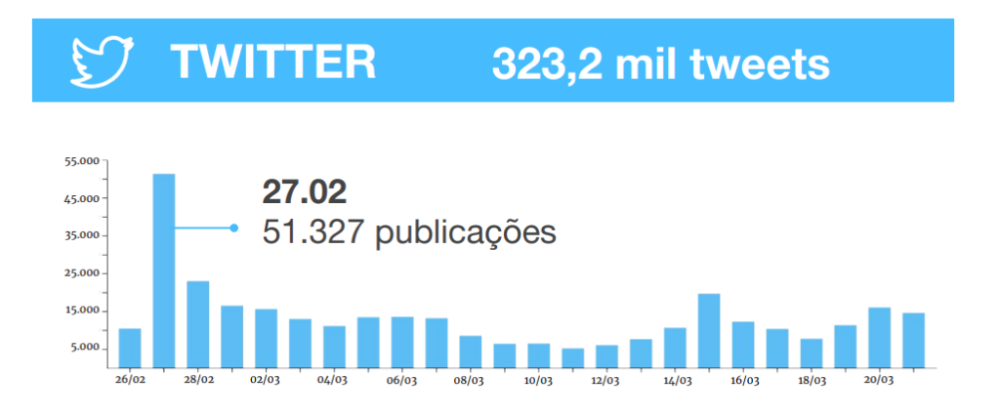

On X, after the start of the campaign, the volume of messages reached 323.2 thousand in the first week. Although it decreased later, the flow of conspiracy content remained constant, focusing on vaccine manufacturing laboratories.

One example cited by the survey is the tweet published by podcaster Jamile Davis, in which she states that “the CEO of Pfizer had to cancel a visit to Israel because he is not vaccinated. I will repeat: The CEO of Pfizer is not vaccinated!”. The post, published on March 1, 2023, reached 178.7 thousand views, in addition to registering 7 thousand likes, 2 thousand shares and 172 comments.

The publication highlights that the information was taken out of context. “The news was taken out of the context of the first quarter of 2021, when Albert Bourla had in fact canceled a trip to Israel because he had not yet received the second dose of the vaccine.”

Another example mentioned is the tweet published on the profile of Dr. Roberta Lacerda, stating that the “artificially inoculated Spike protein is present not only in the deltoid muscle but also in the testicles. Where there should be sperm, there are small cavities filled only with spike protein.” The post, published on March 2, 2023, reached 291.8 thousand views, 5 thousand likes, 2 thousand shares and 207 responses.

The research highlights that Lacerda shared the theory of toxicity of the spike protein, being synthesized in the vaccination against Covid-19. “She used the video of a German research to suggest that vaccination would have an impact on fertility.”

After the start of the campaign led by the Lula government, the volume of tweets decreased, but remained constant in the first week of March, with conspiratorial content focused on vaccine manufacturers.

An exclusive research conducted by Agência Pública, published in March 2021, exposed the inequality between white and black people regarding the number of people vaccinated against Covid-19 in the country.

According to the study, the number of white people vaccinated against Covid-19 exceeded that of black people. The study analyzed data from 8.5 million individuals who received the first dose of the vaccines authorized to combat the coronavirus.

In addition, approximately 3.2 million people aged 18 or older who identified as white received the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. On the other hand, 1.7 million individuals who identified as black, aged 18 or older, were vaccinated with the first dose of the coronavirus vaccine.

Impacts of vaccine misinformation on black and poor communities

Misinformation about vaccines has proven to be a growing problem, especially in black and peripheral communities, where the effects of misleading content are amplified due to structural factors and lack of access to reliable information.

Comprova's editor-in-chief, Sérgio Lüdtke, and Aos Fatos' chief reporter, Luiz Fernando Menezes, analyze the extent of this phenomenon and its impacts on public health.

Lüdtke highlights that the most widespread misinformation in these communities is related to the supposed side effects of vaccines against Covid-19, in addition to erroneous information about immunization policies for other diseases.

“We also found misleading content about vaccination policies and the distribution of vaccines for dengue and mpox, known as monkeypox,” he explains.

Regarding how this misinformation spreads, the editor-in-chief points out that its reach is highly personalized, depending on specific networks and the profile of the person publishing or sharing the information. “The effect of misinformation varies according to the user, influenced by the level of information they have and even by their degree of emotional fragility,” he says.

In the fight against misinformation, Lüdtke draws an analogy between traditional vaccination and “immunization” against rumors. “The vaccine against misinformation consists of clear and reliable information, explanatory content and a lot of context, offered even before the emergence of misinformation campaigns,” he suggests.

He emphasizes that public entities must act preventively, anticipating risks and preparing the population with solid information to avoid harm to public health policies.

Regarding the role of digital platforms, Lüdtke proposes more rigorous actions, such as intensifying the moderation of content that is harmful to health and adopting measures such as fact-checking, deleting harmful profiles and issuing specific warnings.

“It is necessary to alert people who have accessed or viewed content that has subsequently been proven to be harmful or dangerous,” he adds, highlighting that such initiatives could significantly reduce the impact of disinformation on the most affected communities.

The head of reporting at Aos Fatos, Luiz Fernando Menezes, points out that the spread of disinformation in these areas may be more intense due to a series of structural factors.

“Unfortunately, there is no systematic survey on disinformation according to race or gender in Brazil,” he says — but mentions some studies that have already explored the topic.

According to DataFavela, 64% of residents of poor communities reported having come across disinformation about public policies. In addition, Fala Roça highlighted that the lack of access to media education in favelas and peripheral areas makes these communities more vulnerable to disinformation. Menezes also notes that factors such as illiteracy and poverty, which affect the black population to a greater extent, aggravate the situation.

“Illiterate and poorly educated people tend to consume content differently — they prefer videos and audio over texts,” he explains. As a result, these people often end up getting their information through platforms like WhatsApp, Instagram, and TikTok, where information can be easily manipulated without strict control.

The lack of clear policies against misinformation on these platforms, as is the case with WhatsApp and TikTok, allows any user to share misleading content without proper verification.

“Unfortunately, traditional fact-checking work, which is closely tied to written media, does not reach these communities with the same strength,” laments Menezes. To combat this phenomenon, Aos Fatos has sought to diversify the ways in which it distributes its fact-checks.

“We try to adapt ‘classic’ fact-checking to more accessible formats, such as stories on Instagram, threads on X, and even videos on TikTok,” says Menezes. Furthermore, he highlights that it is essential that the government and digital platforms also get involved in campaigns to combat vaccine misinformation, as it has generated serious consequences, such as refusal to vaccinate and the return of diseases.

Changes to Meta's anti-misinformation policies

The head of reporting highlighted the importance of intensifying the moderation of content that is harmful to public health on digital platforms. He mentioned as an example the partnership that Meta, the parent company of Instagram, Facebook and WhatsApp, has with fact-checking agencies, which identify and flag misinformation posts after careful analysis.

“It is important to strengthen content moderation. Vaccine misinformation can kill, and in some cases, it stops being just a rumor and becomes a real risk to public health,” he warns.

However, on January 7, the big tech announced a change to its platforms, which consisted of ending the fact-checking program and replacing it with a system called “Community Notes”.

Inspired by the model already implemented by Elon Musk's X platform (formerly Twitter), the new format puts users at the center of moderation, allowing them to identify and add context to potentially misleading content. The change has already come into effect in the United States.

In a video posted on social media, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg justified the decision as a return to the company's roots in terms of freedom of expression. With the new system, Facebook, Instagram and Threads users will be able to collaborate in flagging questionable posts, shifting the responsibility for moderation from agencies and experts to the community itself.

“It's time to return to our roots around freedom of expression. We're replacing fact-checkers with Community Notes, simplifying our policies and focusing on reducing errors. Looking forward to the next chapter,” Zuckerberg wrote when posting the video on his Instagram account.

Still, on the subject, Menezes emphasizes that the solution involves measures such as reducing the reach of false content, demonetizing or even deleting posts, when applicable.

In addition, the journalist advocates that platforms promote content that debunks fake news, since fact-checking often does not reach the same number of people as false information. “The ideal would be for fact-checking content to reach the same audience as fake news.”

The importance of vaccination and tackling misinformation in black communities

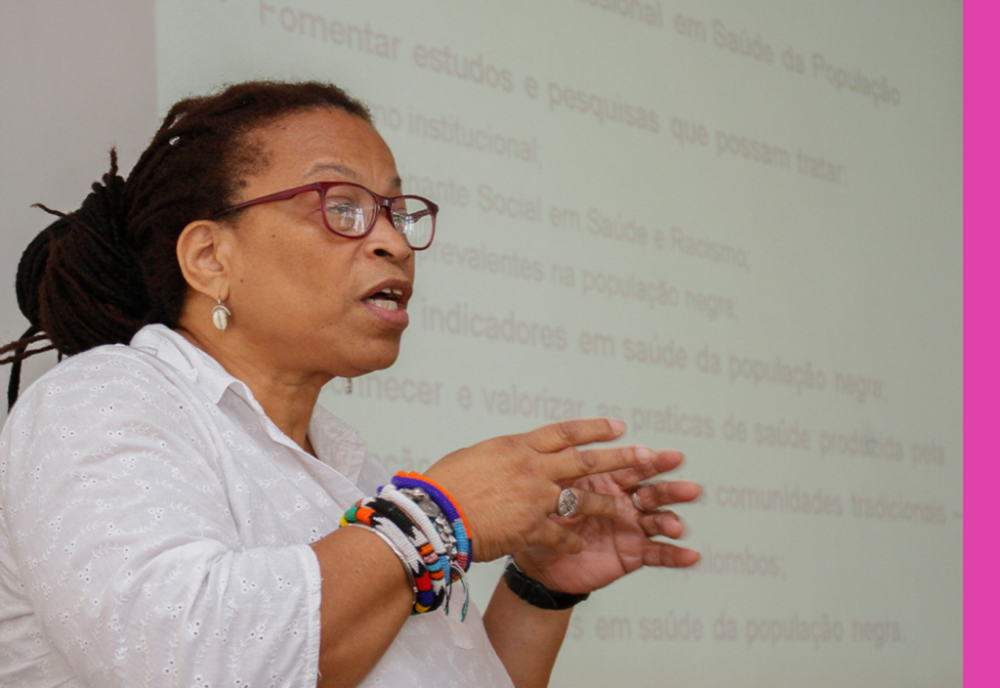

Lúcia Xavier, general coordinator of Criola, one of the main organizations fighting racism and promoting the rights of black women, highlights the importance of vaccination coverage for the black population.

“Vaccination is essential, especially for children, as it is what allows us to address the first and most critical moment of infant mortality,” she said. For Xavier, the primary healthcare network, made up of hospitals and basic health units, plays a crucial role in this process, especially for the black population in vulnerable situations.

Lúcia Xavier, general coordinator of the Criola organization (Picture: Reprodução/Social Medias).

Lúcia Xavier, general coordinator of the Criola organization (Picture: Reprodução/Social Medias).

She also emphasizes the importance of strengthening ties with health units from prenatal to postpartum, as this continuous monitoring is essential to guarantee vaccination and access to health care. “These ties must be strengthened to ensure that children are enrolled in the health system and thus receive the necessary immunization,” said the coordinator.

Misinformation about vaccines, especially in peripheral communities, was also mentioned as a major challenge. The coordinator reveals that Criola is implementing a project in the municipality of Japeri, in Rio de Janeiro, to raise awareness about the right to vaccination, focusing on two vulnerable groups of the black population: children and the elderly.

She believes that the initiative will help ensure that these communities make informed decisions about the health of their children and families. In addition, she highlights the need for educational campaigns focused on combating misinformation, considering the high rate of preventable morbidity and mortality in poor communities.

She also stressed that vaccination campaigns need to be culturally adapted so that information can be delivered efficiently and respectfully. “It is not enough to simply disseminate information; we need to ensure access to the vaccine and overcome discriminatory stigmas,” she says.

Lúcia also mentions the historical distrust of the black population in relation to the Public Unified Health System (SUS), which despite being the main provider of care for this population, faces challenges such as institutional racism.

“The SUS is a fundamental policy, but for it to truly fulfill its role of promoting health and dignity, it is necessary to address institutional racism, improve accessibility and ensure welcoming care,” she concludes.

Inequality in access to health care and the misleading discourse on vaccination

The member of the Immunotherapy Department of the Brazilian Association of Allergy and Immunology, Marcos Gonçalves, discusses the factors that contribute to the disparities in vaccination coverage between black and poor populations compared to the more privileged.

According to him, “the difficulty of access by the black population and those living in areas to the health system” is one of the main factors responsible for the disparities in vaccination.

For the specialist, although the Public Unified Health System (SUS) should be accessible to everyone, in practice, it faces logistical and structural failures, such as the shortage of vaccines and the difficulty of accessing health clinics.

Gonçalves also highlights the influence of fake news, which has negatively impacted the population's confidence in vaccines: “Unfortunately, a portion of the most vulnerable population does not have the resources or the discernment necessary to distinguish what is true from what is false.”

According to him, false information spread by videos of politicians and other influencers discredits vaccines, making it difficult to combat misinformation.

Regarding the history of inequalities in access to health care, the specialist points out that the most vulnerable populations face significant obstacles, such as “health centers located far away, lack of appointment slots, and lack of infrastructure at the centers.”

For the immunologist, these challenges result in limited access to health care and vaccination, especially for those who depend on the SUS, in contrast to those who have access to private health plans, where care is faster and more accessible.

Regarding preventable diseases, he highlights the risk of re-emergence of diseases such as measles and polio, in addition to mentioning the outbreak of meningococcal meningitis type B that occurred in 2023 and extended into 2024.

The lack of access to the vaccine against this disease, which is not on the SUS calendar, mainly affected the most deprived communities. “More than 90% of cases occurred in children from more economically vulnerable neighborhoods, such as Benedito Bentes, Trapiche and Jacintinho, [peripheral neighborhoods of Maceió], many of them of black origin and belonging to low-income families,” he says.

How to avoid falling for vaccine misinformation?

Researchers from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) and three National Institutes of Science and Technology launched a guide for health professionals in March 2024: “Health misinformation: are we going to tackle this problem?”.

The document addresses health misinformation, especially the devaluation of science and health policies, offering a curation of courses on media literacy, spaces for checking news and reliable sources to guide professionals’ actions in demystifying this information.

See below for tips on how to counter health misinformation:

Consult reliable sources and avoid sharing information without verifying its veracity and origin;

When correcting information, engage in constructive conversations, listening and understanding concerns to adapt your communication effectively;

Whenever possible, use proven data and research to reinforce your message;

Show openness to learning and correcting information, if necessary, strengthening your credibility;

Be patient: changing beliefs takes time and requires repetition and ongoing support;

Health professionals also educate. Teach how to identify and avoid misinformation;

Encourage media literacy for critical consumption of information;

For more help, visit the website of the Ministry of Health.

🎯 To boost your skills and knowledge in the area of countering disinformation, register for our free, self-paced course:

Author: Jean Albuquerque - Graduated in Journalism and a degree in Portuguese Language, resident of the outskirts of Maceió (AL) and postgraduate in investigative journalism from IDP. With experience in proofreading, editing, reporting, early childhood and independent journalism. His work has been published in UOL (TAB, VivaBem, ECOA and UOL Notícias), Agência Pública, Ponte Jornalismo, Estadão and Yahoo.

Background photo: A health worker prepares a dose of the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine against COVID-19 in Brasilia on September 13, 2021.— Evaristo Sá/AFP