Anti-refugee narratives

To understand selected narratives in the context of the humanitarian crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border (also in Lithuania and Latvia), it is important to structure the terminology used to describe people trying to enter the European Union. Who is a refugee and who is a migrant? Anti-refugee language has emerged in the public space: the term "nachodźcy" (a Polish play on the word 'refugee' meaning 'aggressor') which appears regularly among nationalists; and the comparing refugees to "thieves and robbers" in certain religious circles.

Refugees or migrants?

Currently, there are attempts to portray refugees as people migrating only for a better economic existence or even as those who want to annihilate European culture and Christianity. Who then are refugees?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights gives the possibility to apply for asylum, and the Refugee Convention established the principle of non-refoulement and non-return of refugees to places where their lives are in danger. Refugees, thus, are people who, as a result of violence, war, persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinions, or belonging to a particular group, seek refuge in other countries.

There is no uniform definition of the term "migrants" but the most important distinction between migrants and refugees is the motivation for which they come to a given country. Migrants usually leave their country to join their families, look for work or education. Migrants are also people who leave a country because of a natural disaster or poverty. Unfortunately, some countries use the term "migrants" to refer to refugees as well. This blurs the distinction between these groups, justifying the lack of application of international law to protect refugees.

‘Aggressors’ (Polish: ‘Nachodźcy’)

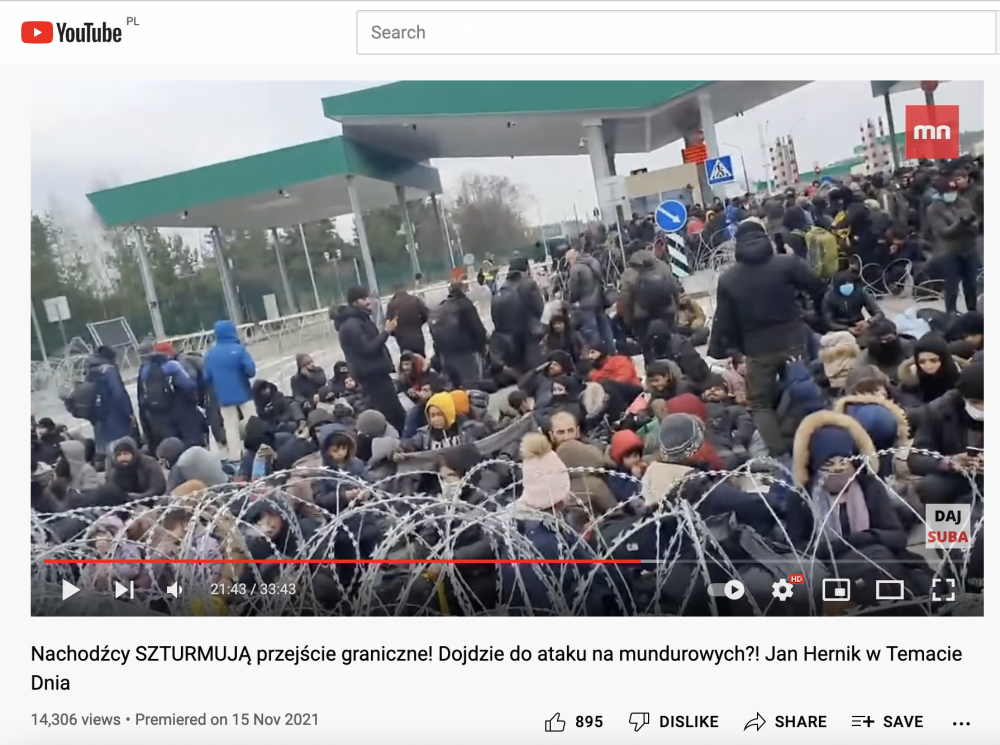

A narrative of 'aggressors' has emerged in the Polish-Belarusian border crisis. This phrase appears on social media suggesting that refugees are invading and attacking Poland. One can encounter comments like this one (by the host of the program on the video below): "You can see this crowd of migrants, or rather "aggressors" controlled by the Belarusian authorities."

One of the leaders of the nationalist movement, called for building a wall to protect Poles from 'aggressors'. He suggested that refugee 'aggressors' are "part of Russia's hybrid war against Poland." From the content, it should logically follow that the refugees are actually victims. Instead, this story has a tone of warning in opposition to compassion. It also evokes fear of the people exploited by the Belarusian and Russian authorities.

What is resonating from the new anti-refugee narrative being used in nationalist circles?

“The refugee 'aggressors' are an inferior group to the migrants;

In Polish, 'nachodźca' (refugee aggressor) means someone who is an uninvited stranger or even an invader and aggressor;

refugee 'agrgessors' are simply being 'controlled' by the Belarusian authorities. However, the soldiers standing with guns and the announcements about the possibility of using force against these people prove that the refugees are forced, not steered. You can 'let yourself be steered' by someone, but 'being forced' means experiencing violence from someone - being forced to do something.

"Thieves and Robbers"

Refugees in the Christian tradition are usually considered a group that needs special care and protection. However, in Poland, at the peak of the tension along the Polish-Belarusian border, there were voices calling refugees "thieves and robbers." A simple analogy was drawn: refugees who stand in front of barbed wire and try to cross the border illegally behave like "thieves and robbers". One cleric wrote: "The door is used for peaceful entry. (...) Those who stand at the door and wait for our permission accept that this is our home, our sheepfold, our rules - and show by this that they respect our territory and our rights. Anyone who gets in by any other means is a thief and a robber. They have no honest intentions."

Anti-refugee religious narratives are dangerous socially. This is because they draw on the authority of a "holy book" and are voiced by clergy endowed with authority. Churches and communities are places for building relationships and a deep sense of belonging. This means that anti-refugee opinions and interpretations sink deeper into people's beliefs and make them more difficult to analyze rationally.

Anti-refugee narratives then and now

The previous years were characterized by narratives about dangerous refugees, who in fact were not found in Poland. The refugee fear narrative was thus a fictional one that had no basis in fact, but still had an impact on the collective imagination.

Current anti-refugee narratives are still based primarily on fear and turn the people exploited and deceived by Belarusian authorities into aggressors and invaders. However, it is a documented fact that the Belarusian border services force refugees to destroy barbed wire and attack with tear gas and stones the Polish services guarding the border. Even the personal involvement of the Belarusian services in these attacks has been documented.

Alternative narratives and counter-narratives of activists and NGOs

The current crisis is a humanitarian and political crisis. Activists and NGOs highlight this in alternative and counter narratives by highlighting facts, appealing to ethics or morality. Below are selected examples of counter narratives about the "evil refugee" and the refugees who are "thiefs and robbers".

People like us

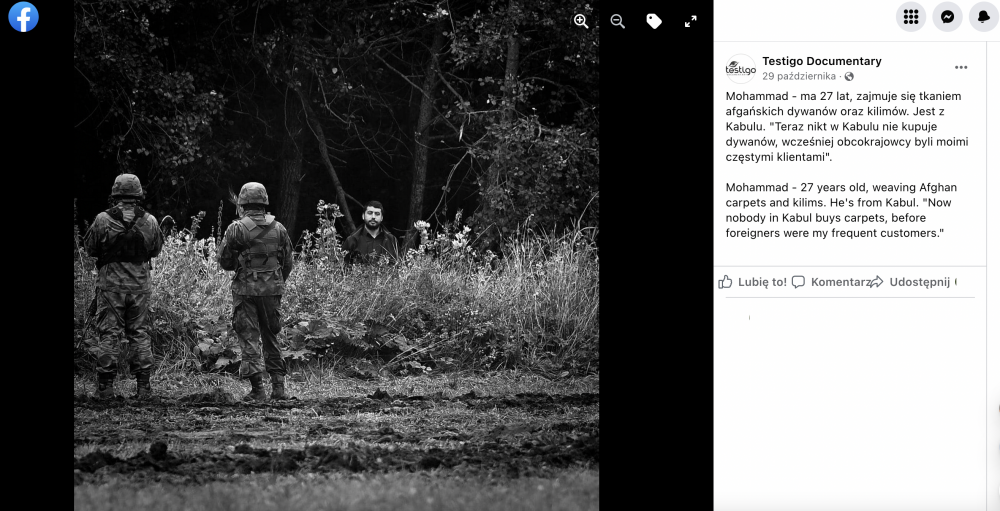

The journalistic collective Testigo Documentary photographed five Afghans staying at the Usnarz village border (with their consent) showing that refugees are "people just like us". This narrative appeals to facts (who they are) and creates a positive image of refugees (ordinary hardworking people).

Where are the children?

It is an emotional narrative that appeals to ethics and morals. This question was asked in relation to families with children being taken back to the border. A photo of one of the children - a girl in a soiled jumpsuit - particularly moved the parents. Photos of families with children appeared on social media along with the hashtag #WhereAreChildren. The Parents Without Borders group decided to use a symbolic black and white drawing of a girl in a jumpsuit drawn by a befriended graphic designer.

The green light

The green light has become a symbol of hospitality and rescue. Refugees have been told in numerous social media groups that when they see such a light on a house, they can go there to eat, dry off, or charge their phone. Over time, in various campaigns across the country, individuals are encouraged to turn on a green light or put up a green lantern instead of a profile picture on social media as a sign of solidarity with refugees at the border. This narrative alludes to the fact that there are people in the woods on the border who need help.

The lesson

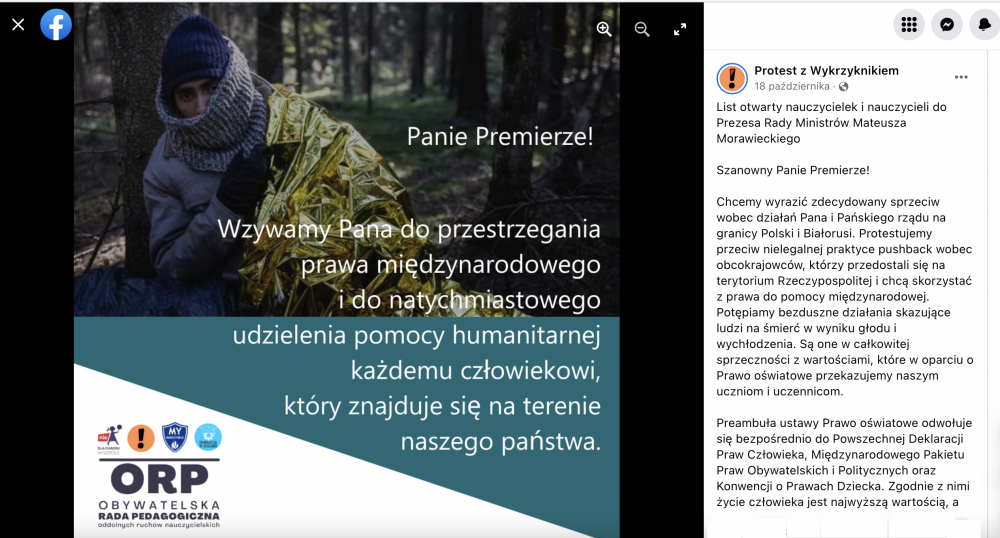

In protest of the illegal pushbacks of refugees at the border, teachers wrote a letter to those in power reprimanding the Prime Minister. They wrote that he was teaching the public a bad lesson. The teacher groups' action referred to moral responsibility of leaders in the decisions they make.

Prayer without borders

"An Open Letter of Christians to Sisters and Brothers in Faith on People Affected by the Humanitarian Crisis at the Eastern Border of Poland" was initiated by clergy, journalists, publicists, artists, and social activists. In contrast to voices in churches criticizing the granting of asylum to refugees, the letter and the encouragement to pray together addresses the inseparability of spiritual and practical help to humans by quoting the New Testament: "Faith, if it has no works, is dead in itself."

"No one deserves to die in the woods" campaign

Actors, journalists, musicians, artists and a bishop recorded a short spot in which each person asks for humanitarian aid to be allowed to refugees at the boarder. At the end of the spot, we hear an emotional phrase: No one deserves to die in the forest."

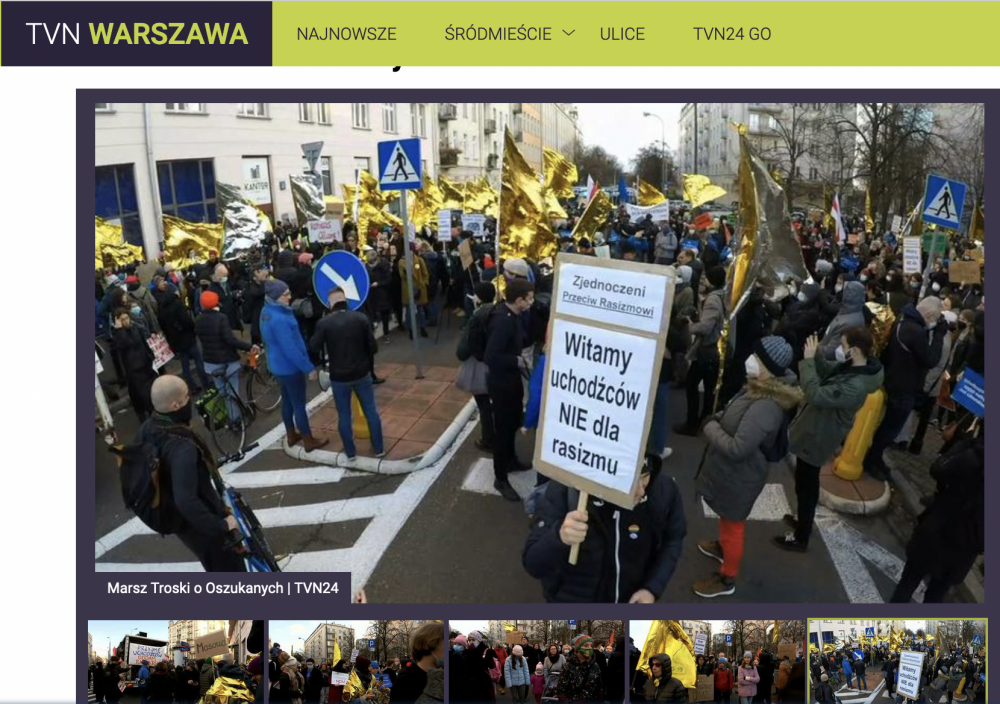

March of Caring for the Deceived

NGOs and informal groups working with refugees or playing a supportive work on the Polish-Belarusian border organized a march in Warsaw. They called it the March of Caring for the Deceived. They created an alternative narrative to make the public aware that people on the border are people deceived by Lukashenko, not invaders or agressors. The symbols used during the march were silver and gold foils used to warm up the frigid people and green lights to symbolize relief actions. Additionally, people were encouraged to use the hashtag #HumanityHasNoBoarders - an emotional reference to the need to be human towards refugees.

https://tvn24.pl/tvnwarszawa/najnowsze/warszawa-marsz-troski-o-oszukanych-5496804

Background illustration: Compilation of photo by Ahmed akacha from Pexels and photo by Pixabay from Pexels / Pexels license